Pete Celi’s Premier Guitar Article – A History of Doubletracking

Our own Pete Celi is at it again—tracing today’s popular guitar effects such as flanging, echo, and chorus to the early days of tape recording studios.

Free US Shipping On Orders Over $49

Easy 30-Day Returns

Financing Available Through ![]()

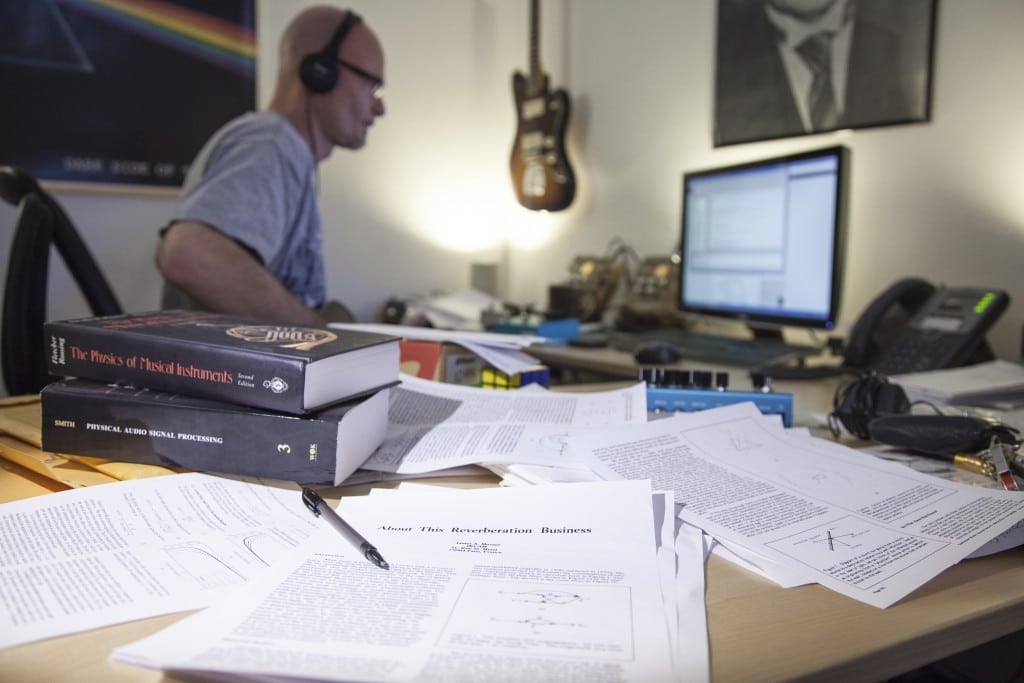

Strymon co-founder Pete Celi is responsible for the sound design and DSP algorithm creation for all the Strymon pedals that use DSP. Recently I had the pleasure of sitting down for an interview with Pete. We discussed his approach to sound design, his background in music and technology and the path that led him to what he does at Strymon today, as well as his love of electric guitar.

Pete, can you please talk a little about yourself, where you’re from, what you’re into?

I was born and raised in Massachusetts and started playing guitar as a kid. I went to college there and studied electrical engineering, and moved down here [to Los Angeles] in ’89. There’s your short answer!

What made you decide to move to LA?

It was really the call of music that brought me out here. I’d graduated college in 1985 with an electrical engineering degree, and started working for Analog Devices, the chip maker [in Massachusetts]. I did that for three years. All the while I was playing guitar, jamming with friends, little projects here and there. But Analog Devices was a very kind of serious button-down environment that just really didn’t feel like it was for me for long-term, and I decided to move out to Los Angeles to go to Musician’s Institute in Hollywood. So Analog Devices was actually a pretty prestigious place to work in my field, with good pay, good benefits, and I quit that job to go to Los Angeles with no real plan other than to attend Musician’s Institute.

What was your experience at Musician’s Institute like?

It was actually a really great experience because I got to really see… see some reality. They split us up according to ability, and I ended up traveling around with sort of the top class of about 20 guys. But I could see that the top few guys in that class were not only light years ahead of me in terms of playing ability, but also had this spark of creativity and genius in their playing. I realized that even those guys were gonna be struggling to try to do something in music, and I knew I’d never attain their level of naturalness and musical ability. So that was valuable to me because it became clear that, ok, I’m not gonna be a professional musician. But it was a fun year—it was kind of like a sabbatical. I got to learn some things and have some fun, but then I needed to figure out what I was gonna do next because school was over and I didn’t have a job.

Pete in 1989

Pete in 1989So how did you end up staying and surviving in Los Angeles?

I knew there were some companies in L.A. that made music products, and I had an electrical engineering degree. So I wrote some letters and signed them with my name and telephone number and mailed them to a few different places, and one of them that called me was Alesis. I ended up working for them starting in 1989, at an exciting time when everything they were doing was breaking performance and cost barriers. The original Quadraverb had just come out. A few years later the ADAT came out, and the company grew from about 30 employees when I started working there, to about 200 employees. It was a rocket ride, and it’s what got me into working with music technology, and that’s what I’ve been doing for about 26 years.

We were designing our own chips at Alesis, which was pretty cool and kind of rare. But the chips I would be working on would maybe be used in a product two or three years down the road that hadn’t even been defined yet, so I never really got to have my hands on actual products. So it was fun and a great environment, but I never really felt 100% connected to what I was doing. I felt like I was working on technology, but not really working on music products. Writing DSP (digital signal processor) code and working on sound design for music products like I do now was really a pretty dramatic change for me.

After Alesis, you worked for Line 6, right? What did you do there?

My title was Senior DSP Engineer. When I started there, Variax was really a blank paper project. They told me they wanted me to start researching how they could take what they did with [emulating] amps and do it with guitars, and two or three years later: “Hey, this actually works!” I wrote all the DSP sound generating code for the original Variax. Getting involved with that, writing DSP code for a product and being instrumental in shaping the sounds of that product really felt a lot more true to what I really wanted to be doing.

And now you are one of the co-founders of Strymon. Why do you feel like this is the ideal fit for you?

At Strymon I get to wear two hats and create the DSP code and also do the sound design, so instead of having those two things separated into two departments (sound design and engineering), they really are one and the same thing, so there’s nothing lost in translation. To know exactly what sound you’re going for as your write the code, and to know what you’re hearing when you listen to the sound and how to address it in the code is ideal. At Strymon we’ve got a small group. The guys that I’m working with here are guys that I’ve known, that I have great respect for, a creative group of guys. There’s a lot of collaboration.

So I assume you’ve done the sound design for every Strymon pedal from the beginning?

Yes, well with the exception of OB.1, where Gregg did the analog design, because OB.1 is a fully analog pedal. I provided input here and there on the sound, but Gregg did the analog design for that product. But other than OB.1, for all the other products that have come out since we started the Strymon line, 100% of all the sound processing and sound design has been done by me.

Can you describe your approach to sound design?

The way I look at what we’re doing is, we’re designing effects where fundamentally the goals and the process in a broad sense aren’t different than those of any other effect maker designing in any other medium. If you’re an analog designer, you start with an idea, you have a circuit, you build it, you have components, you have some knowledge base and history to draw from, and you make adjustments and listen for things and decide when it is to your liking or what direction it needs to go in. We’re doing things in a similar way, except that the medium is DSP, which does allow us greater flexibility and possibilities, ultimately.

How do you research and what is your process like?

We have tools to draw from and experience to guide us in certain ways, but it’s definitely not a robotic process like, “well this is how we do it, we just put these signals in here…” It’s different for each sound. For something with a physical or electrical counterpart, like a spring reverb or a power tube tremolo, there are more measurements and equations that are part of the process, but we’re not trying to capture an exact copy of a specific existing piece of equipment.

So once we have described the process mathematically, the next step is to craft the sound. For a tube tremolo, different oscillator topologies might distort the LFO waveform in a good way. Or the amplitude of the LFO can be varied while different tube biases are experimented with, just as an amp designer would do. So a fair amount of the process is artistic as well. Crafting the sound.

I think the cool part about DSP is that it’s so open, that there are so many things you can do, and it’s easy to experiment and try things that wouldn’t have been easy to do before. For many effects, like on the BigSky reverb, some of those reverbs have long abandoned the reality of any physical space. It’s about creating resonances and pitches and feedback and ambient soundscapes that don’t have any physical counterpart. That can be the most fun because it’s really just an exercise in creativity and freedom.

Can you talk about any particular challenges or successes you’ve experienced with any of the Strymon pedals?

Well, early on in the technology of the Strymon line we developed what we call the dBucket technology, which is digital bucket brigade delay technology. In an analog bucket brigade delay, they use chips that are called bucket brigade chips because basically there’s a transfer of charge through a transistor and capacitor, many many times, like old-time firemen with each man passing water from his bucket into the next guy’s bucket, so this analog signal is transferred through each transistor and capacitor stage, and that takes time, and the signal is delayed.

Each bucket stage adds time, and the rate at which signal is passed from bucket to bucket is controlled by a clock. If you speed up the clock, everything goes faster and there’s a shorter delay, or slow down the clock and you get a longer delay. It’s fundamentally different than a digital delay where traditionally you’re running at a fixed clock rate, and you sample things in and store them in memory, and if you want a longer delay time, you just use more memory, or in the bucket analogy, you just add more buckets, but it’s always the same rate, and there’s no loss from bucket to bucket in a digital delay.

A big part of the character of an analog delay is the fact that it’s running on this variable clock system where the number of buckets stay the same, but it’s just how fast you’re running through the buckets. So to get long delays, you actually have to slow down the clock enough that you start to hear artifacts, and there are two different kinds of artifacts. One is actually the clock itself, if it is slowed down into the audio frequency range you’ll actually hear the whine of the clock, but more than that the other type of artifact is if the clock speeds get slow enough, it starts to alias.

Can you explain aliasing?

Aliasing is where in a clocked system, which actually applies to an analog delay because it is a clocked system, the maximum frequency that can be represented accurately is one half of the clock frequency. If you go higher than that, what comes out of the system is actually a frequency that’s wrong. It’s kind of like when you watch an old film and you see the spokes of a wagon wheel and they look like they’re going backward, because the spokes are moving too fast for the frame rate. That’s aliasing in film.

So in an analog delay if you’ve got a slow clock speed, let’s say 10kHz, any input signal above 5kHz is going to alias, and it sounds like “bzzzzzzz,” a buzz coming down from those frequencies. So in order to combat that in analog delays usually they employ a lot of filtering to remove those high frequencies so that content that would be reported erroneously is filtered out. So that’s why analog delays are traditionally dark sounding. It’s not something to do with the chip, it has to do with the filtering they put in there to reduce those artifacts.

On top of that, to continue with the bucket analogy, you spill some of the water each time you transfer from bucket to bucket, and that’s due to the physical properties of the transistors and monolithic capacitors that are doing those trasnfers. How much you spill is dependent on how much water is in the bucket, and how fast you are transferring from bucket to bucket, so it’s a complex process in some ways. That’s something I know about because I have a background in integrated circuits and stuff.

That ‘water spilling’ creates the grungy and noisy aspect of analog delays. So we thought, let’s do a delay in DSP that’s actually running internally at a variable clock, and include a bucket brigade line where the loss between transfers actually occurs as it does in the chips. And we figured that out, and it does work, and what it allows you to do is to control that loss. You can make it a perfect transfer, or you can make it a not so good transfer from bucket to bucket. You can get a different range of experiences. It’s still a variable clock process using a fixed number buckets, but because it’s in DSP we can control the quality of the bucket brigade chip, the amount of filtering, the companding parameters, and the various levels of artifacts. So that was really a big thing for us, once we got going, we were like, this is really cool.

What do you think led you to finding that you had a real passion for sound design?

My whole life I’ve played guitar and I’ve always loved it and I’ve always been obsessively tuned in to the response between your fingers and what comes out of the speaker, and what the effect is doing, and all that kind of stuff. And never in the 38 years since I started playing guitar have I ever taken two months off, like “I’m not gonna play.” I probably play guitar three hours a day just for work. I guess it’s always been in my DNA.

When I was 13 or 14 and just learning to play, I was taking lessons from my neighbor and he had been letting me borrow this crappy acoustic, and one day I went over to his house and he had this Silvertone electric guitar and a Silvertone amp that had a reverb. He handed the guitar to me and said “why don’t you play this and see what you think.” It was the first time I’d ever held an electric guitar. And I played a note and there was some reverb on, and it was one of the few moments of my life that I still remember so clearly, because it was so electric, and I was like, DAMN! It was probably a seed for why I’m doing this now, because… That was COOL! It’s been a constant thing throughout my life since then, regardless of all the other variables.

Subscribe to our newsletter to be the first to hear about new Strymon products, artist features, and behind the scenes content!

Our own Pete Celi is at it again—tracing today’s popular guitar effects such as flanging, echo, and chorus to the early days of tape recording studios.

Our very own DSP Engineer and co-founder Pete recently wrote an awesome article on flangers for the September issue of Premier Guitar. It illuminates some

Soon we will be releasing our El Capistan dTape™ Echo. To capture the full experience and complexity of a tape echo machine, every last tape

14 Responses

Awesome stuff. This guy’s work has had a huge impact on me as a guitarist and as a musician. I take my Blue Sky and TimeLine from Portland to Guatemala and back, and couldn’t imagine life without them.

Great piece. What a treat for those of us with a love affair with Strymon’s products, to get a glimpse into both the technology the man who crafts it. Pete is an inspiring and inspired guy.

Inspiring stuff, great to see someone truly harmonise the subtle nuances of traditional analogue integrated circuit design with the modern capabilities of DSP.

Was unaware Pete Celi had already made a considerable impression in the audio engineering field in Alesis and Line 6, very interesting!

This was a very interesting read and congratulations to Pete Celi for his outstanding work of which I own a lot. Is that a redwood Telecaster next to a redwood tree in image 2? Very nice if so.

As an EE serving as Principal Eng. and HW Eng. Manager in global companies and a weekend warrior musician myself, I really have a ton of respect for what Pete has achieved. I look forward to his “OD + Fuzz” MIDI pedal to compliment the Mobius, Timeline, and Big Sky. Hey I KNOW you can beat the TC Electronics Novadrive I am currently using on my MIDI rig with these particular Strymon pedals – so lets see it… a Vibe pedal would be nice too! 🙂 Also, I have ALL your pedals and while the Flange and Chorus don’t see much use anymore, and the Lex and El Cap are limited to certain things… for impromptu and flexible live gigs I have to say THANKS especially for Deco, Brigadier and Dig… I use these a LOT. Best regards, Keith

Very interesting interview, thanks! I own the BIG SKY, bought it shortly after it came out. It’s such a great pedal, i’m enjoying it so much! By the way, the Strymon demos on Youtube are fine!

Thank you for this interview. Very interesting reading.

Thankyou so much Pete Celi and everyone at Strymon for your superb technology and inspiring demos.

There are literally hundreds of effects available these days but none that I have heard have that really special mojo Strymon pedals have.

There seems to be a curious quality of sound found in every Strymon pedal that links them all together!

It would also be great to be able to have the possibility to store some of the sounds we create .. around 30 sounds would be fine..in something like a “Strymon Sound Saver” unit..perhaps connected from the outputs of any Strymon pedal before going to amp(s) with a digital number readout?

Just a weird idea for the future ! 😉

Very Best Wishes from Germany!

I take my hat off to Pete Celi and the Team! The passion and artistry is showing through the luxurious sound and construction of the effects. To me they have the attributes of fine instruments.

Thanks Matt for writing this up, and Pete for doing the interview! Lots of insights here. I’m a hardware engineer working on motherboard design, and a lifetime guitar tinkerer. Quite the fun read!

Would love to know something about the tele with a strat neck and the jazzmaster in the office.

Hi Eric, I’ll work on getting more info on those and post some pics on Instagram with their story 🙂

fantastic and real story….

just got back to seriously playing again now that the kids are grown up…

never been much of a pedal person, however recent purchase of Big Sky and DIG

have changed my mind on pedals…wow is all I can say.

thank you for what you do….

Thank you so much for sharing that. Really great to hear and if you post any of your songs please share them with us.